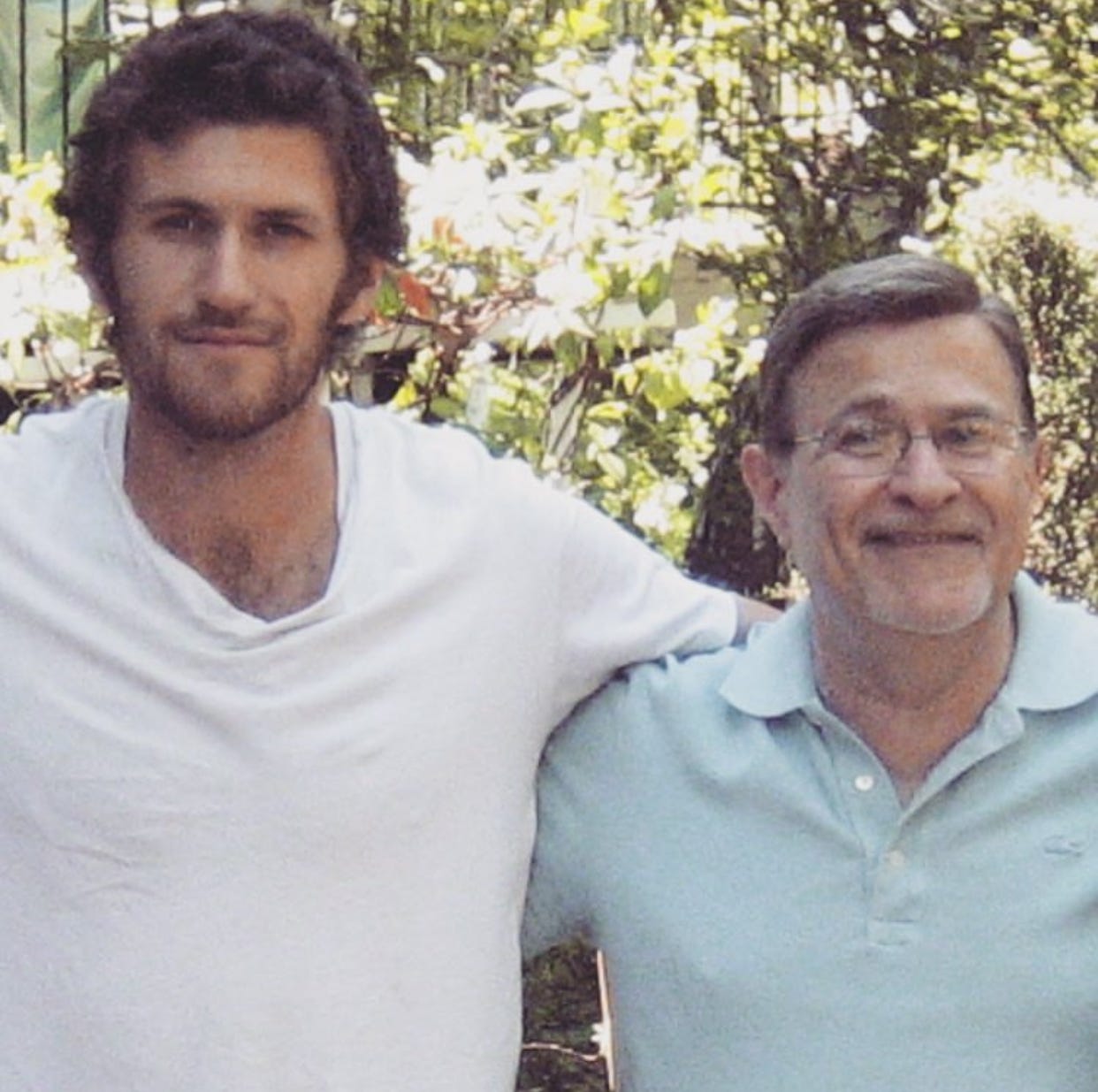

A couple years after my dad and Elena became lovers, he returned into my life to resume being my father. Besides his cheerier mood, the most noticeable change was that he was no longer bald. The wraparound crown of hair he had been sporting since before I was born was now completed with a new puzzle piece on top. Sometime in the few years we hadn’t spoken, he had started paying a wig woman to regularly glue a silver-fox toupee onto his scalp with a neat side part. A George Clooney attempt for a man who primarily dressed in Kirkland clothes from Costco. But he actually did look kind of dashing. His hair lady was unmistakably an artist who seamlessly integrated his existing hair with the complementary piece. And before we go any further, let me confess that I hate to give looks too much influence in matters of the heart. To fall prey to this narcissistic society that advertises appearance insecurity for capital gain is a sore spot. But it’s also naive to pretend that a visual on a person doesn’t communicate important things. So what did this new hairpiece say? It gave my dad a chance to be seen through new eyes. You had to adjust to his change and reevaluate his person with the time that had changed you. Basically, his fake hair forced me to confront my dad as a person who wanted to be loved.

His head fuller in appearance and unseen aura brighter, he was doing that thing where people who are happier than you try to hide their joy out of respect for your baseline misery. Parading an “aww shucks,” humility out of good taste but with happiness spearing out in bright strobes of light. This disco ball effect was a marked contrast from the last times I’d fallen away from him. I had remembered him spiteful and petty. One argument or another repelled us from each other. It had been years of simply not talking when we reunited at one of my brother’s junior college baseball games in the San Fernando Valley. I took in his new look “You grew out your hair,” I joked.

The meeting had been arranged after making recent inroads via text messages to each other. My brother Travis brokering the deal. It wasn’t unfamiliar this ceasefire agreement. Our relationship had been back and forth like this since my early adolescence when my mom divorced him and told me he was the worst man in the world after Bill Clinton. She could have been right too, I don’t know. We all have different relationships with the men we marry and the ones who contributed to our births. But I was a man now, a young one, forming into my own. I was also alone in the world and open to the extra support a father could provide in a society modeled after patriarchs. So we met up and maybe because of that paternal conditioning, the repairing of our relationship turned out to be pretty painless. He took my sister Britt and I out for regular lunches, got candid, apologized for his past mistakes, and started loaning us the few hundred bucks he’d always been such a reluctant bastard about ever since the divorce soured everything in our lives including family finances.

He was several decades older than his final girlfriend Elena when they became an item. I’m not sure he ever told her his exact age and I’m not sure she asked, but they knew the years between them were vast. This was before the age gap discourse on social media would have skewered him if he’d been an internet presence, which he wasn’t, aside from surfing it anonymously. The numbers are just short of daunting though, I admit. She was not a young woman but she was not an older woman either. Numerous lifetimes separated Michael and Elena and yet they found each other in this lifetime. What was one to think? He told me how what they lacked in similarities they more than made up for by marveling at one another’s differences. Did he put it that poetically? No. But he helped bring me into this world and I owe it to him to do a little script polishing. He was a more sensible man than a poet, he lived alone off the Westlake exit of the 101 freeway, past a Caruso shopping mall, in one of the many lookalike stucco and Spanish tile roofed suburban tracts in a gated condominium with homeowner’s association fees. Elena stayed with her daughter at her parent’s place down by the strawberry fields and salty ocean breezes of Oxnard. Both of them were employed by the county in mental health services but rarely interacted at work, and only ever hit it off because they were seated next to one another at a staff- wide training on sexual harassment.

But they began what they became over shared footlong sandwiches at a Subway near their offices. He would give her half his turkey footlong and she traded him half her...I don’t remember her sandwich preference. What I know of her is mostly what he told me. He said Elena was always so pleased by those simple lunches at Subway, in a way his more demanding partners had never been. Each of them tearing off six inches of their own lives in between bites of Recession busting five dollar footlongs. Bonding over past failures as adults tend to do. Each of them were in the throes of relationship dissolution. Elena’s husband had fled back to Mexico, leaving her to raise their young daughter, Isabella, alone. Dad was sifting through the most recent rubble of his newest ex-wife, a verbally- abusive senior citizen with a drinking problem, who took more of his money (per day spent married) than either of his previous two marriages.

As these lunches blossomed into a weekly ritual, I don’t remember him telling me who finally made the first move; reached out and touched the other’s elbow, gripped their moist palm, prolonged the warmth of a friendly hug, or clumsily leaned over the table to breathe the other one into their own lungs. What I do recall is the plain fact that Dad and Elena started a romance together, threading through the industrial buildings and fertile agricultural beds of Oxnard.

I started calling him Dad again. In the earlier years of my parent’s divorce, while they were still waging war against one another, my mom insisted on my siblings and I calling our dad by his first name, Michael, as a means of disrespecting him. Michael, insisted on us not doing that. So at some point we stopped using his name altogether. We would just say, “Hey,” and then start our sentences, parrot my mother’s demands, express our own saccharine wants. It never grew less uncomfortable. This stalemate between both of our parent’s disapprovals maintained through a decade plus of awkward addresses, until a year into reconnection with my dad as a grown man, getting to know him for the first time, and realizing this guy was one of my best friends, I had to give him a name. Dad, I named him.

In my early twenties with Dad back in my life better than I’d ever had him, I learned that resentment, no matter how tightly clung to, is a tension that can be knifed apart with even the smallest of gestures to the contrary. To his credit, my dad made those gestures to the contrary, and to my credit, I accepted them. He had been made better by love. His trademark sardonic bitterness had waned into a gentler irony. He was finally adored by a woman whose feelings he returned and finally accepted by his brood of now grown kids. It was good timing, all of that, because my dad was also old. He had less time than his vigor suggested. In relation to the dreaded numbers who torture time, my dad was much older than Elena, and his kids, and even the rest of the guys in his weekly men’s group. He kept pace with the young, sure, but my dad was born in 1940. His father was carried like a bundle of babka from Russia into America as a baby in 1901. I’m almost forty at the time of this writing and Dad, Michael, the one in this story and inscribed in my DNA, has been gone for almost ten years now.

While writing this first draft in pen a few years ago, when I was younger too, my scribbling took on the haphazard shapes of his messy psychiatrist’s scrawl. I suppose this recollection of his memory to be its own prescription. One I’m writing to continuously deal with the echoes of my own heartache. He was once more than my stories of him though, he was once real and out of my control.

He bought her jewelry at Costco. Pink gold, it said on the receipts as we cleaned out his home in the days after he passed. Money and being needed and losing money to feel needed were his love languages. Elena’s was tenderness, she didn’t care about money. He told me she just wanted to be held and encouraged. He told me how thrilling it felt when she called him her “Man.” He learned little bits of Spanish for her, bought her the furniture she needed after she found her own apartment and evidently jewelry from Costco. She took him to a Pitbull concert and taught him about putting Valentina hot sauce in a bag of chips and shaking it all together. He kept bottles of it in his fridge door for her. It was too spicy for him but he was in awe of her style. He fixed her bagels before we’d come over on Sundays and she’d be halfway through one about to leave to go to places I’m not sure? I’m not sure why she’d leave so shortly after we’d come over on the Sundays. Church? Her daughter? I told you, most of what I know of her I learned from him. We were both visitors to a man centered in a world that suited him. He didn’t wear his CPAP machine to bed when she slept over. Took his vitamins every day, wore his hairpiece, still more or less cared for his seven young adult children to keep himself young. Maybe we overwhelmed her? He rode the stationary bicycle each morning with his friends at the gym, always behind a physical copy of the L.A. Times that he was pedaling slow enough to read. In our oversharing moments my Dad claimed he still didn’t need Viagra to get it up even though we never asked him to present those details like that. Maybe he said something like, “Elena is my Viagra,” I can’t be sure but it seems familiar. Laughing all the time, I remember laughing all the time about immature things and the catch 22’s of this hypocritical society and disappointing life. Making fun of players on the Lakers together. This Eastern European basketball player getting injured snowboarding in the offseason and how coach Phil Jackson called him a “Space Cadet.” Then our thick accented impressions of the guy trying to not so coyly make inquiries to his coach about possibly going snowboarding again. Gossiping about other family members who weren’t there. I’d call him anytime I had a long drive across the city ahead of me and we’d shoot the shit. Talking to and seeing him in those days, it became easy to love my dad because he was so actively involved in his own mundane-ass life. It was inspiring, how if he could, he would have gone on forever in his boring as fuck routines among good enough material comforts and the excitement of having a lover who he adored a couple nights a week.

But things started to cool off with my dad and Elena. After a few years together she would bring over her daughter on the weekends. That was the closest they became to a family. My dad would take Isabella to the mall, he made her laugh, fixed her snacks. “I’m more of a father to her than her own father,” he told me on numerous occasions, his son. But they weren’t progressing beyond the weekends. Those initial sparks with Elena were starting to fade into a weekend routine that wasn’t cutting it anymore. They considered a scenario he told me, of Elena and Isabella moving in with him but never seriously enough. He didn’t want there routine to progress much beyond the weekends they already had. It was a rhythm he found ideal at this stage in his life but Elena was still in the stage of life that wanted to build a life. I’d like to lay all the blame on age but it was also just my dad. Aside from these pragmatic incompatibilities starting to rear their inevitable head, his own simple nature always turned out to be his Achilles heel romantically. Old or not, he was a man who craved sameness even if the women he chose romantically, and the children he made, spoke to the contrary.

The things we fall in love with are sometimes the same things that drive us away and my dad’s stability was most appealing to women at their most vulnerable, but once they were healed it numbed them. He then resented these wild women for getting back to themselves under his steady hand which they then reached for less and less. Also, I suspect he must have already begun quietly feeling the release of a malignant body in his pancreas. Elena, because she was the kind of woman who intuited the holistic and understood the body (she once recommended I take corn silk supplements for my kidney stones and, as a natural diuretic, they helped) also seemed to sense the change in his vitality too.

Elena’s affections toward Michael took a turn and it began to plague his concentration and already failing health. He had been through this before with women he loved less and relayed to us his newest insecurities about his queen. She was still in the prime of her life, not pretending to be, like him. She was not sick either, she exuded a full bodied vitality, so his body must have begun to feel glaringly diminished in contrast. He tried to brush off this logic and intuition as he talked himself in circles to us. He hoped it was just one of her moods. “She’s just very thoughtful is all,” he would tell us as a counter to his fears, trying to downplay her growing distance. She would take her journal to the beach in Port Hueneme near the Naval firing range when she needed reflection. My dad said he could usually mark on a calendar the two to three days she’d be cranky in a month. “Women are hormonal creatures.” he’d tell my brothers and I as though speaking some kind of ancient wisdom. But this new discontent of hers was lasting longer than a period.

Elena broke up with my dad months before his cancer diagnosis and thank God for all parties involved. Even in his moments of sensible reflection, he was relieved not to have her worrying about him and to worry about. In more vulnerable moments, he also openly admitted that if he could just get healthy, there would be another one of Elena, or Elena again herself, legs spread fertile juicy heart pulsating with love on the horizon if he kept surviving against all odds. He wanted one more. He wanted love like it had just been made. He would despair and then hope and reflect and confide. He’d even drive out to that same beach near the Naval firing range and “ask the Universe for a messenger” then post a photo of a seagull on his Instagram. Evidently, men are hormonal creatures too.

He stopped going to the wig lady. He shaved his head entirely bald before the chemo did it for him. He looked holy, he looked whole. He realized he should have done it a long time ago. I remember coming over and him yanking off his hat like a Catskills comedian with a big smile on his face and laughing with him at the reveal. He had transitioned furthest into himself by appearance just months before the ravages of the disease started eating away at it.

Dad lasted two years and one month with pancreatic cancer and almost beat the damn thing. All at the cost of physical and psychic torture. To undergo chemotherapy with a broken heart must have been a deeper hell than he even let on. In fact, he had been carrying himself so valiantly in the face of such monumental loads of toxic medicines, radiation, surgery, and romantic loss, his friends started calling him “Iron Mike.” I think they coined that nickname ironically because my dad was a lover not a fighter, a meek man at times even, but also because they, like all of us, could see his register of fear. He wasn’t ready to die. He told us that over and over, even if his relationship already had.

But what about us? What about me? How were he and I? How must men center themselves to love each other in a society that never teaches us anything but the centering? After Elena left him but before he left us, I remember the afternoon he told all his offspring about the cancer. I didn’t cry until I got away from him. His emotionally devastating announcement was met with my outward sympathy but also a tearless refusal to allow him the permission to give up. I was also ready to torture him. It was my turn to ask him to enter longer bouts of pain so I could selfishly keep him alive. We had been apart long enough and I wasn’t ready for our next inevitable fissure to become permanent.

In the fast twitch muscle of our lives talking all kinds of inane bullshit, my brother Travis and I sat by our dad’s side at every doctor’s appointment, chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery. We watched him attentively as he handled some insane combinations of treatments. We stood like bodyguards next to him so that death couldn’t visit too long, while the medicine made cold foods too cold for him to touch and acupuncture was the only thing that gave him back his appetite. He would photocopy crossword puzzles from the L.A. Times and we’d all sit there as the poison rushed into his port and we’d each fail at finishing the thing. Trav and I accompanied him and fostered the goal of getting his tumor reduced enough in size to be operable and we did it. He did get the markers down. He made it to the Whipple Surgery which proved to be our greatest hope and his last stand.

If you don’t know, pancreatic cancer is just about a death sentence. In the still primitive forms of treatment where competent surgeons had to feed one more body to the next steps of figuring out how to handle the disease, he sacrificed his body for hope and medical advancement. The Whipple Procedure reorganized his organs and altered him irretrievably, but he was for a few weeks declared cancer free. We didn’t know the deal. Why didn’t he seem relieved? It angered me. I hadn’t yet learned how a win, no matter how mighty, will inevitably turn to a loss. The procedure turned him into a diabetic like his father had been, forcing him to inject with insulin before every meal he could stomach. He had me watch him do it in his car in a parking garage before getting pastrami sandwiches. His father died of a heart attack. He always thought he’d go the same way. His mood soured and energy depleted after his own sweet insulin was taken from him. All just so that the cancer could return months later and wreck him. Micro-spread they first called it.

In those last months of his life, bitterness and fentanyl patches invaded my dad’s thoughts. “I’m not even going to see who wins the Super Bowl,” he moaned to me alone in his bedroom weeks before he’d prove himself right. “I had money on Dallas.”

Pessimism arrived. He snapped at us in ways large and small for mentioning our hopes for his continued life while equally damning us for inching toward the acknowledgement of his impending death.

The pain medication increased and the pharmacists eyed me skeptically while picking it up for him with my greasy hair and careless attire during an opioid crisis. Dad’s enthusiasm for our crude humor waned, that’s how I knew it was bad. The man, always quicker with a dirty quip than the rest, had become too sick to be a sicko. When I asked what he wanted me to do with the little remaining chunk of his money left to me after being divided seven ways, three divorces, a bankruptcy, recession, bad investments, and seventy plus years of life, he said he didn’t care. One afternoon alone in his living room, near the end, looking like a skeleton, he lashed out at how my brother Travis and I were the two laziest people he’d ever met. That we lived like princes in our cheap apartment we scored years earlier together in Venice Beach. My dad had encouraged us to continue arranging our lives around his fading one and then have us shit when we’d admit our finances weren’t in order enough to need to borrow a little money for rent from him.

He was angry because he had fought and lost and was tired and drugged and his legs swelled up with fluid and I’d massage them and he’d tell me I had nice hands.

He’d apologize for his calloused words a few days later in lucid moments in those final days, “Josh, I can just see how hard this is wearing on you. I just won’t be here to help you anymore. I don’t want you eating out of a dumpster one day.”

Elena had been gone for awhile by the end. Gone, except in my dad’s brief yearnings to know she still cared about him. How he’d cradle her supportive text messages with his voice as he insisted on reading them to us and commenting on how kind she’d been to reach out occasionally. He refused to see her though, didn’t want to cry, or be remembered by her as an ill old man. He had once been a healthy old man who looked and felt younger than he was. He had once fooled the Gods and hid from father time beneath a glued on arrangement of hair.

I want to go back one more time. Before this inconvenient illness, in the brilliant twilight of a man seeing his life climax later and luckier than most, how when he was still an old man pretending to be young, in those glorious days of reconciliation and intoxicating love, when my world was still filling up with overwhelming amounts of strength for his loss to eventually sap. When he’d first told me about Elena as though seeking to be absolved for the age difference between the two of them. “You should see the way my friend’s wives looked at us. They didn’t even try to hide their jealousy.” And did I absolve him? Yeah, why not? He deserved a romance after all those years in failed ones. Elena? I don’t know what she deserved. I didn’t know her much outside of his words. She deserved only love like all of us do. No, she deserved more than all of us because she gave my father the best love of his life and returned him to me with enough momentum to make things right. Who was I to judge an adult relationship that inspired all that? No matter how wide spanning its elements like father time, privilege, and disparity of license within a given society. Even at the risk of a skewering from the chronically online, the hordes of keyboard warriors impervious to the mysterious swamps of human hearts and the orchids that rise up out of them. I can’t say it was wrong because I am stuck in the world of my father, refusing to leave his emotional principles and moral conveniences. Who am I to be the arbiter in such matters of his flesh and hers when it increased kindness, gentleness, and understanding into the world? Their spirits finding enough significance to pause on one another after collecting and forming for billions of years, enough for me to witness and through all the harsher elements find beautiful.

In those best days of his average American male lifespan, he’d take her to Mexican resorts for a weekend now and again. How afterwards, in the pits of his decay, he loaned her money for a car, as he was dying. He did that for all of those he loved, loaned his family money for their used cars. As he was living and as he was dying. Even my mom, fifteen years after their divorce and all the ugly scars strewn across. Months before his death, he forgave her of a recent car loan, when through tears that broke past even the numbing gates of fentanyl patches he said to me “She gave me five kids, you guys were the best gifts I could have asked for.” Used cars and their maintenance were his love language, brief emotional lucidity was his miracle.

Elena, hers was tenderness, he told me that, I told you that already, tenderness, and he did love her in a tender way. He loved her nevermore than when he told me, I remember this much, how she would calm his worries about their doomed age difference and whisper sweetly to him in the middle of the night to just enjoy who they were together in the healing pitch of their sightlessness.

How on the day he died he waited for me to arrive, departing from his body as soon as he heard my voice boom into his bedroom like a canon. How after firing off his release, I held him, told the vanishing man it’s ok, laid him back with my brother, wasn’t afraid of his death only being heartbroken the rest of my life. How minutes after his passing, a hummingbird flew into the house behind the front door I’d left open in my haste to see him one last time. The hummingbird from the feeders on his patio on the complete other side of the subdivided unit below, it circled through the interior of his condominium and my sister Britt said “What the fuck is that?” My brother said “It’s a hummingbird, it’s Dad.” As what was left of his body lay in front of us, with him departed.

Telling that story of the hummingbird at his memorial service. Drinking so many beers in defiance of him and his old cautions about the horrors of “having a wooden leg.” Basking in my false resilience by not going down permanently, staying on my wooden feet. Elena showed up there in mourning too, alone, with no one by her side. She was so brave for coming alone. Polite as always, a strained expression on her face, almost like she was yearning to say many things to me but emptied of the impulse of where to begin.

So I’ll finish what I wish was there in her thoughts through the memories Dad shared with me. I’ll introduce what he told me about in the vapor of their evaporating time— she and him at a resort in Cabo, all-inclusive, drinking sugary cocktails. Reclining on beach chairs, free of envy, free of pain, sand between his ample body hair and tickling along her saltwater skin, the last strong waves of a good life as Michael Allen Turek cresting up and down embalming Elena with admiration and gratitude. Their hearts, those human fickle hearts beating in unison for their moments in agreement, something resembling ease. How in those two days three nights, as I’m recollecting what he shared with me, trying to live within his life for him because I miss him doing it for himself, I see the two of them composed in one another, educating one another’s spirits for their different travels ahead. How sweetly patronizing their holy love must have been in those moments they were in recognition of it together, in their voices and in silence and in relief.

Such a beautiful depiction of love met in an unconventional way. Thank you for sharing. It’s an honor to read it

beautiful to see your U-turn back to your dad. i'm not there yet, and don't expect to be. but i will be beside at his death if time and distance allows. i'm particularly interested in family dysfunction when at least one parent is a psychiatrist. my father was one. he abandoned us emotionally when together, then physically after my parents' divorce. long story short, he relocated to nigeria and took vows to become a catholic priest, leaving my mom to be my brother's caretaker alone. i've yet to meet anyone with a psychiatrist parent and a healthy family unit.